The First 7 Years Will Make (or Break) Your Child's Future...

How To Break Free From iPad Battles And Reclaim Your Child's Precious Early Years In Just 21 Days

(even if you've tried everything else and nothing has worked)

The Story Behind The System That's Transforming SCREEN-ADDICTED KIDS Into THRIVING KIDS In Just 21 Days

"I Don't Want to Play With You Anymore, Mom... I Just Want My iPad."

Those words shattered my heart as my 6-year-old son slumped deeper into the couch, his face illuminated by the blue glow of his screen.

The creative, energetic little boy who used to spend hours building LEGO cities and chasing butterflies had disappeared into a digital void.

I slid down against the wall, tears streaming down my face, remembering how just months ago he used to beg me to play pretend and read stories together.

Now our daily battles over screen time left us both exhausted and defeated:

Every request to put down the iPad sparked an epic meltdown

He'd lost interest in all his favorite toys and outdoor activities

Playdates turned into kids sitting silently side-by-side on devices

His attention span for anything non-digital had shrunk to minutes

The sweet connection we once shared had been replaced with conflict

Every morning, I'd wake up determined "today will be different," only to find myself caving in to avoid another tantrum.

I tried everything other parents suggested:

Setting strict time limits (he found ways around them)

Using screen time tracking apps (they just caused more fights)

Going "cold turkey" (the meltdowns were unbearable)

Replacing iPads with "educational" apps (still addictively glued to screens)

Reward charts and behavior systems (nothing could compete with the digital dopamine hit)

Each failed attempt left me feeling more hopeless and guilty.

Was I a terrible parent for letting it get this bad? Was I damaging him forever?

Then I Discovered Something That Changed Everything...

While desperately researching childhood screen addiction at 3 AM, I stumbled upon groundbreaking research about the developing brain and digital stimulation patterns.

What I learned shocked me:

According to groundbreaking neuroscience research, the first 7 years of your child's life quite literally shape their entire future. During this critical window:

90% of your child's brain architecture is formed - and excessive screen time can permanently alter its development

Essential social skills and emotional regulation pathways are being wired - or potentially damaged

Core personality traits and learning abilities are being set for life

The foundation for future relationships, career success, and happiness is being built

But most terrifying of all:

Most parents are unknowingly using methods that not only fail to solve screen addiction but actively damage their child's development during this precious window

I know because I was making all these same mistakes...

Through extensive research and consultation with:

Child neuropsychologists

Digital wellness experts

Childhood development specialists

I discovered WHY traditional approaches fail - and more importantly, what actually works.

I call it the "Digital Detox Formula"

By working WITH your child's brain chemistry instead of against it, I was able to:

End the daily screen time battles without constant fights

Help my son rediscover his love of creative play

Restore our close parent-child connection

Watch him choose real activities over screens

Create healthy tech boundaries that actually stick

After helping thousands of other families replicate these results, I've refined this system into a step-by-step method that anyone can use...

...even if nothing else has worked before.

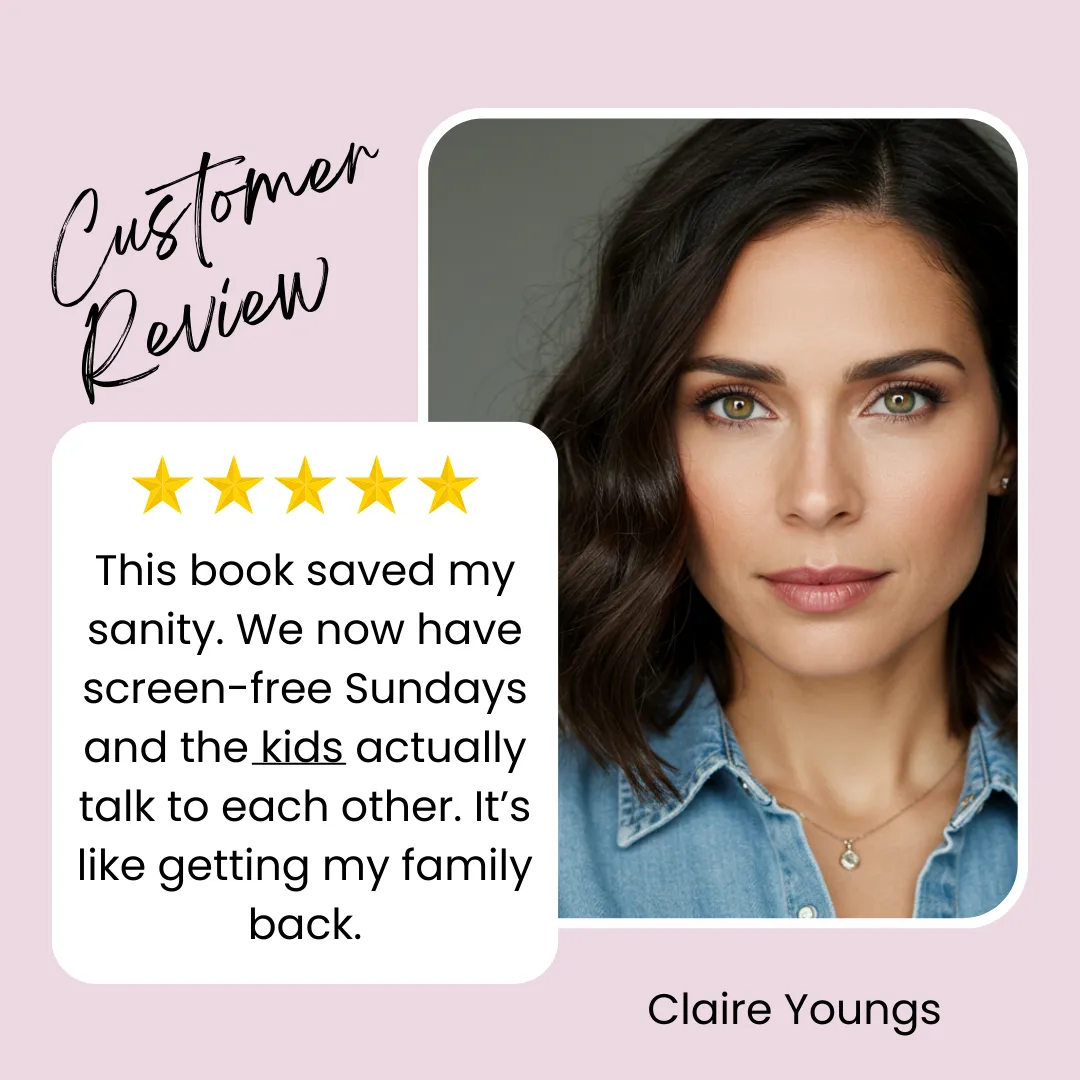

But don't take my word for it. Listen to these parents:

THE SKILLS THAT SEPARATE THRIVING KIDS FROM STRUGGLING ONES

The 4 Essential Skills Your Child Needs (That Screens Are Destroying)

Emotional Intelligence & Social Skills: The ability to read facial expressions, understand social cues, and form deep connections - what scientists call the #1 predictor of lifetime success (and what excessive screen time actively destroys)

Real-World Problem Solving: The confidence to navigate challenges without digital crutches - essential for developing a resilient, adaptable mind (increasingly rare in today's screen-dependent children)

Focus & Deep Attention: The capacity to concentrate, learn deeply, and resist digital distractions - crucial for academic and life success (and what's most at risk during the critical 0-7 window)

Creative Play & Imagination: The foundation for innovative thinking and emotional processing - vital skills that diminish with every hour of passive screen time

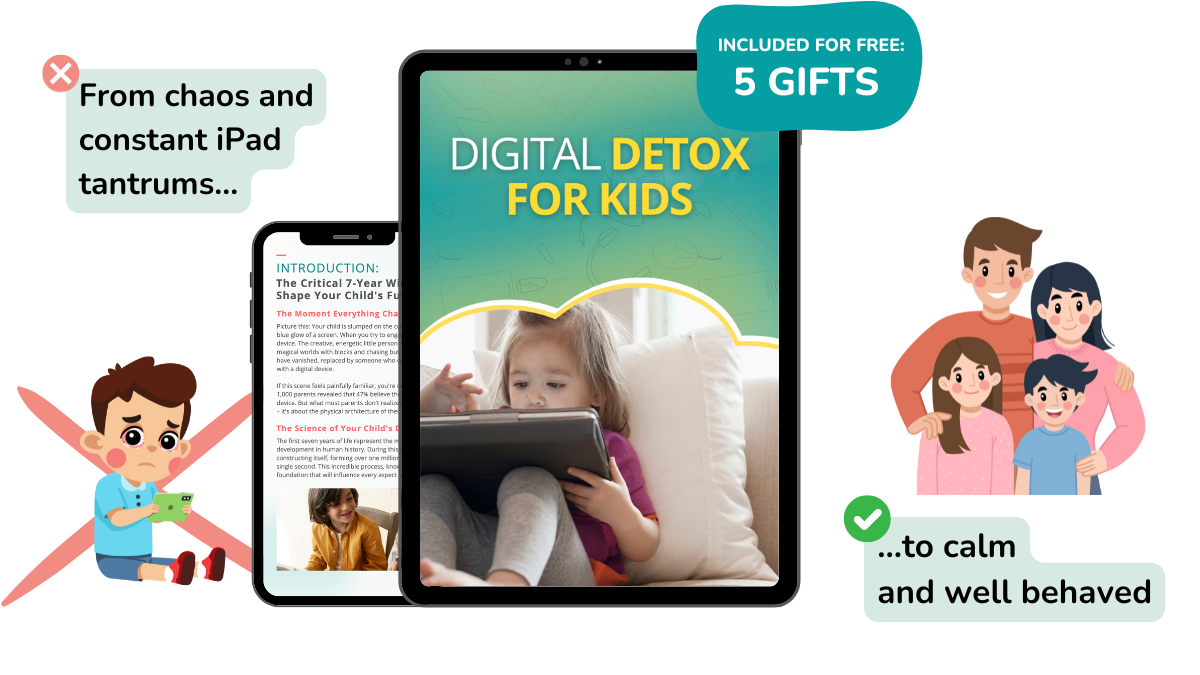

INSTANT DIGITAL ACCESS - START TRANSFORMING YOUR FAMILY TODAY

Here's Everything You Get With The Digital Detox Formula Today!

What's included:

The Complete Digital Detox Formula: 7 proven modules that rewire screen addiction and restore family harmony

🎁 Plus These 5 Essential Bonus Guides 🎁

"The Screen-Free Activity Bible" - 100+ engaging alternatives that captivate kids more than devices

"The Calm Parent Protocol" - Handle screen-related meltdowns with confidence using proven de-escalation techniques

"Social Solutions Guide" - Navigate playdates, family gatherings and school situations without screens

"Tech-Healthy Toddler Toolkit" - Special strategies for preventing screen dependency in younger siblings

"The Family Connection Reset" - Rebuild your bond with proven bonding activities and conversation starters

Normally: $97

Today: $7

BEFORE AND AFTER

The Transformation You Can Expect

Don't let screens continue dominating your family life. Your relationship with your child can be stronger than ever - you just need the right system to make it happen.

Before The Digital Detox Formula:

Daily battles over screen time

Constant meltdowns and tantrums

Child only wants digital entertainment

Strained parent-child relationship

Guilt and uncertainty about tech limits

Screen addiction getting worse

After The Digital Detox Formula:

Peaceful tech transitions

Child chooses varied activities

Return of creative play and curiosity

Strong family connection

Confident parenting decisions

Healthy relationship with technology

YOUR TRANSFORMATION PATH BEGINS HERE

The 5 Core Phases That Transform Your Child's Relationship With Technology:

Each step precisely calibrated to rewire digital dependency through proven neurological optimization.

Phase 1: Rebuilding Your Connection (Days 1-5)

Watch your child's eyes light up again when they see you - just like they used to before screens took over. This gentle approach helps you reconnect with your little one's heart while naturally reducing their need for screens.

Discover the simple 5-minute ritual that makes your child feel truly seen and heard

Learn how to turn everyday moments into precious bonding opportunities (even during busy days)

See your child start choosing cuddles and storytime over screens within days

Phase 2: From Tantrums to Trust (Days 6-10)

End the exhausting screen battles without feeling like the "mean mom." Our loving approach helps you set limits while strengthening your bond.

Transform screen transitions from meltdown moments to peaceful exchanges

Finally stop feeling guilty about setting boundaries (and see your child actually respect them)

Restore the joy in your relationship instead of constantly being the "screen police"

Phase 3: Rediscovering Real Play (Days 11-15)

Watch in amazement as your child rediscovers the magic of creative play - just like children did before iPads existed.

See your child pick up forgotten toys with newfound excitement

Listen to their imagination come alive during playtime (instead of begging for screens)

Experience the joy of having a child who creates their own fun again

Phase 4: Thriving in the Real World (Days 16-18)

Help your child develop the social skills and confidence they need - without feeling left behind in our digital world.

Handle playdates, family gatherings, and outings with newfound ease

Watch your child make real friends and genuine connections

See them engage confidently in social situations instead of hiding behind screens

Phase 5: Your New Family Freedom (Days 19-21)

Create lasting change that strengthens your family bond and sets your child up for a bright future.

Enjoy peaceful family meals without screen distractions

Experience the pride of raising a child who's present and engaged

Know you're giving your child the best possible start in life

GIVE YOUR CHILD THE FUTURE THEY DESERVE

Get The Digital Detox Formula Now

While other parents struggle with escalating screen battles, you'll be reconnecting with your child using our proven system.

COPYRIGHT 2025 | PDF STUDIOS | PRIVACY POLICY | TERMS & CONDITIONS

DISCLAIMER: Please understand results are not typical. Your results will vary and depend on many factors including but not limited to your background, family situation, and commitment level. All business entails risk as well as consistent effort and action.

NOT FACEBOOK: This site is not a part of the Facebook™ website or Facebook Inc. Additionally, This site is NOT endorsed by Facebook™ in any way. FACEBOOK is a trademark of FACEBOOK, Inc. DISCLAIMER: Please understand results are not typical. Your results will vary and depend on many factors including but not limited to your background, experience, and work ethic. All business entails risk as well as taking regular and consistent effort and action.

Nothing on this page, any of our websites, or any of our content or curriculum is a promise or guarantee of results or future results, and we do not offer any legal, medical, tax or other professional advice. Any potential results referenced here, or on any of our sites, are illustrative of concepts only and should not be considered average results, exact results, or promises for actual or future performance. Use caution and always consult your accountant, lawyer or professional advisor before acting on this or any information related to a lifestyle change or your business or finances. You alone are responsible and accountable for your decisions, actions and results in life, and by your registration here you agree not to attempt to hold us liable for your decisions, actions or results, at any time, under any circumstance.

This site is not a part of the Facebook website or Facebook Inc. Additionally, This site is NOT endorsed by Facebook in any way. FACEBOOK is a trademark of FACEBOOK, Inc.